Some people remain skeptical of the idea that tech debt can be kept low over the long haul.

I’ve noticed that when people say something can’t be done, it usually means that they don’t know how to do it. To help with that, this post explores an approach to keep one major source of tech debt under control.

Tech debt can grow without the application changing

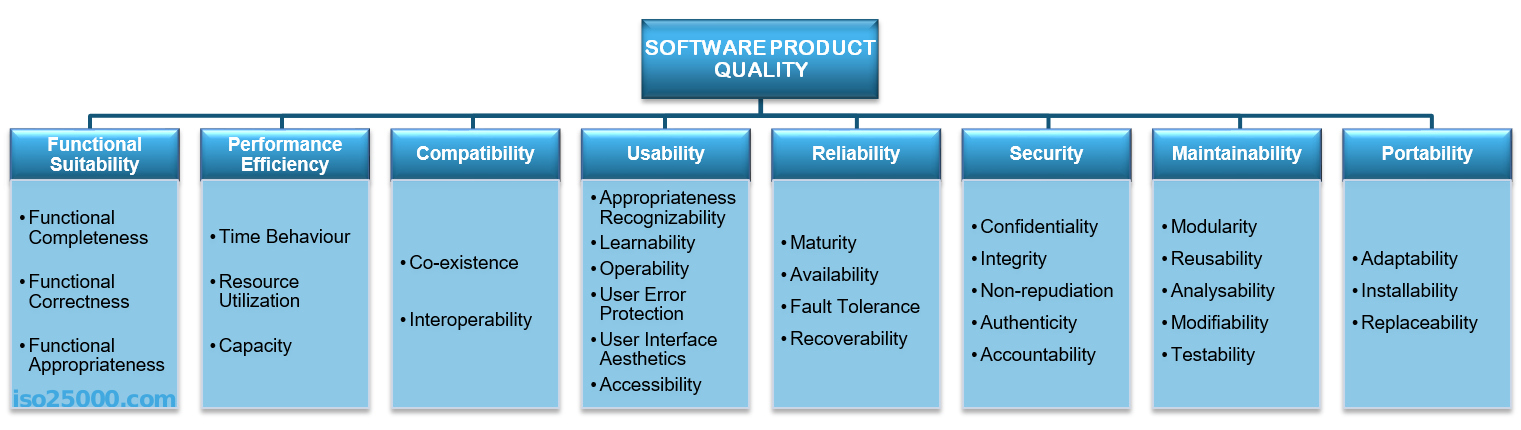

Martin Fowler defines technical debt as “deficiencies in internal quality that make it harder than it would ideally be to modify and extend the system further”. Modifications and extensions are changes and there exist many types of those.

In this post, I’d like to focus on changes in perception. That might seem odd, but bear with me. Let’s look at some examples:

- We are running our software on GCP and our company gets acquired by another that wants to standardize on AWS.

- A new LTS version of Java comes out.

- We use a logging library that all of a sudden doesn’t look so great anymore.

- The framework that we build our system around is introducing breaking changes.

- We learn about a new design pattern that we realize would make our code much simpler, or more resilient, or better in some other way.

These examples have in common that the change is in the way we look at our code rather than in the code itself. Although the code didn’t change, our definition of “internal quality” did and therefore so did our amount of technical debt.

Responding to changed perceptions

When our perception of the code changes, we think of the code as having tech debt and we want to change it. How do we best make this type of change? And if our code looks fine today but maybe not tomorrow, then what can we possibly do to prevent that?

The answers to such questions depends on the type of technology that is affected. Programming languages and frameworks are fundamentally different from infrastructure, libraries, and our own code.

Language changes come in different sizes. If you’ve picked a language that values stability, like Java, then you’re rarely if ever forced to make changes when adopting a new version. If you picked a more volatile language, well, that was a trade-off you made. (Hopefully with open eyes and documented in an ADR for bonus points.)

Even when you’re not forced to change, you may still want to, to benefit from new language constructs (like records or sealed classes for Java). You can define a project to update the entire code base in one fell swoop, but you’d probably need to formally schedule that work. It’s easier to only improve code that you touch in the course of your normal work, just like any other refactoring. Remember that you don’t need permission from anyone to keep your code clean, as this is the only way to keep development sustainable.

Frameworks are harder to deal with, since a framework is in control of the application and directs our code. It defines the rules and we have no choice but to modify our code if those rules change. That’s the trade-off we accepted when we opted to use the framework. Upgrading Spring Boot across major (or even minor) versions has historically been a pain, for example, but we accept that because the framework saves us a lot of time on a daily basis. There isn’t a silver bullet here, so be careful what you’re getting yourself into. Making a good trade-off analysis and recording it in an ADR is about the best we can do.

Libraries are a bit simpler because they impact the application less than frameworks. Still, there is a lot of variation in their impact. A library for a cross-cutting concern like logging may show up in many places, while one for generating passwords sees more limited use.

Much has been written about keeping application code easy to change. Follow the SOLID (or IDEALS) principles and employ the correct design patterns. If you do, then basically every piece of code treats every other piece of code as a library with a well-defined API.

Infrastructure can also be impactful. Luckily, work like upgrading databases, queues, and Kubernetes clusters can often economically be outsourced to cloud vendors. From the perspective of the application, that reduces infrastructure to a library as well. Obviously there is more to switching cloud vendors than switching libraries, like updating infrastructure as code, but from an application code perspective the difference is minimal.

This analysis shows that if we can figure out how to deal with changes in libraries, we would be able to effectively handle most changes that increase tech debt.

Hexagonal Architecture to the rescue

Luckily, the solution to this problem is fairly straightforward: localize dependencies. If only a small part of your code depends on a library, then any changes in that library can only affect that part of the code. A structured way of doing that is using a Hexagonal Architecture.

Hexagonal Architecture (aka Ports & Adapters) is an approach to localize dependencies. Variations are Onion Architecture and Clean Architecture. The easiest way to explain Hexagonal Architecture is to compare it to a more traditional three layer architecture:

A three layer architecture separates code into layers that may only communicate “downward”. In particular, the business logic depends on the data access layer. Hexagonal Architecture replaces the notion of downward dependencies with inward ones. The essence of the application, the business logic, sits nicely in the middle of the visualization. Data access code depends on the business logic, instead of the other way around.

The inversion of dependencies between business logic and data access is implemented using ports (interfaces) and adapters (implementations of those interfaces). For example, accounting business logic may define an output port AccountRepository for storing and loading Account objects. If you’re using MySQL to store those Accounts, then a MySqlAccountRepository adapter implements the AccountRepository port.

When you need to upgrade MySQL, changes are limited to the adapter. If you ever wanted to replace MySQL with some other data access technology, you’d simply add a new adapter and decommission the old one. You can even have both adapters live side by side for a while and activate one or the other depending on the environment the application is running in. This makes testing the migration easier.

You can use ports and adapters for more than data access, however. Need to use logging? Define a Logging port and an adapter for Log4J or whatever your preferred logging library is. Same for building PDFs, generating passwords, or really anything you’d want to use a library for.

This approach has other benefits as well.

Your code no longer has to suffer from poor APIs offered by the library, since you can design the port such that it makes sense to you. For example, you can use names that match your context and put method parameters in the order you prefer. You can reduce cognitive load by only exposing the subset of the functionality of the library that you need for your application. If you document the port, team members no longer need to look at the library’s documentation. (Unless they’re studying the adapter’s implementation, of course.)

Testing also becomes easier. Since a port is an interface, mocking the use of the library becomes trivial. You can write an abstract test against the port’s interface and derive concrete tests for the adapters that do nothing more than instantiate the adapter under test. Such contract tests ensure a smooth transition from one adapter of the port to the next, since the tests prove that both adapters work the same way.

Adopting Hexagonal Architecture

By now the benefits of Hexagonal Architecture should be clear. Some developers, however, are put off by the need to create separate ports, especially for trivial things. Many would balk at designing their own logging interface, for example. Luckily, this is not an all-or-nothing decision. You can make a trade-off analysis per library.

With Hexagonal Architecture, code constantly needs to be passed the ports it uses. A dependency injection framework can automate that.

It also helps to have a naming convention for the modules of your code, like packages in Java.

Here’s what we used on a recent Spring Boot application (*) I was involved with:

application.services

The@SpringBootApplicationclass and related plumbing (like Spring Security configuration) to wire up and start the application.domain.model

Types that represent fundamental concepts in the domain with associated behavior.domain.services

Functionality that crosses domain model boundaries. It implements input ports and uses output ports.ports.in

Input ports that offer abstractions of domain services to input mechanisms like@Scheduledjobs and@Controllers.ports.out

Output ports that offer abstractions of technical services to the domain services.infra

Infrastructure that implements output ports, IOW adapters. Packages in here represent either technology directly, likeinfra.pubsub, or indirectly for some functionality, likeinfra.store.gcs. The latter form allows competing implementations to live next to each other.ui

Interface into the application, like its user and programmatic interfaces, and any scheduled jobs.

(*) All the examples in this post are from the same application. This doesn’t mean that Hexagonal Architecture is only suitable for Java, or even Spring, applications. It can be applied anywhere.

Note that this package structure is a form of package by layer. It therefore works best for microservices, where you’ve implicitly already done packaging by feature on the service level. If you have a monolith, it makes sense for top-level packages to be about the domains and sub-packages to be split out like above.

You only realize the benefits of Hexagonal Architecture if you have the discipline to adhere to it. You can use an architectural fitness function to ensure that it’s followed. A tool like ArchUnit can automate such a fitness function, especially if you have a naming convention.

What do you think? Does it sound like Hexagonal Architecture could improve your ability to keep tech debt low? Have you used it and not liked it? Please leave a comment below.

There seems to be some confusion between Test-First Programming and Test-Driven Development (TDD).

There seems to be some confusion between Test-First Programming and Test-Driven Development (TDD). In the first TDD phase we write a test. Since there is no code yet to make the test pass, this test will fail.

In the first TDD phase we write a test. Since there is no code yet to make the test pass, this test will fail. We may evolve our code using simple

We may evolve our code using simple  All in all I think Test-Driven Development provides sufficient value over Test-First Programming to give it a try.

All in all I think Test-Driven Development provides sufficient value over Test-First Programming to give it a try.

You must be logged in to post a comment.