Last time, we looked at the Red/Green/Refactor phases of Test-Driven Development (TDD).

Last time, we looked at the Red/Green/Refactor phases of Test-Driven Development (TDD).

This time we’ll take a detailed look at the transformations applied in the Green phase.

The Transformation Priority Premise

Most of you will have heard of the refactorings we apply in the last TDD phase, but there are corresponding standardized code changes in the Green phase as well. Uncle Bob Martin named them transformations.

The Transformation Priority Premise (TPP) claims that these transformations have an inherent order, and that picking transformation that are higher on the list leads to better algorithms.

Anecdotal evidence is provided by the example of sorting, where violating the order leads to bubble sort, while the correct order leads to quicksort.

After some modifications based on posts by other people, Uncle Bob arrived at the following ordered list of transformations:

| Transformation | Description |

|---|---|

| {}–>nil | no code at all->code that employs nil |

| nil->constant | |

| constant->constant+ | a simple constant to a more complex constant |

| constant->scalar | replacing a constant with a variable or an argument |

| statement->statements | adding more unconditional statements |

| unconditional->if | splitting the execution path |

| scalar->array | |

| array->container | ??? this one is never used nor explained |

| statement->tail-recursion | |

| if->while | |

| statement->recursion | |

| expression->function | replacing an expression with a function or algorithm |

| variable->assignment | replacing the value of a variable |

| case | adding a case (or else) to an existing switch or if |

Applying the TPP to the Roman Numerals Kata

Reading about something gives only shallow knowledge, so let’s try out the TPP on a small, familiar problem: the Roman Numerals kata.

Reading about something gives only shallow knowledge, so let’s try out the TPP on a small, familiar problem: the Roman Numerals kata.

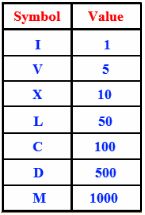

For those of you who are unfamiliar with it: the objective is to translate numbers into Roman. See the table at the left for an overview of the Roman symbols and their values.

As always in TDD, we start off with the simplest case:

public class RomanNumeralsTest {

@Test

public void arabicToRoman() {

Assert.assertEquals("i", "i", RomanNumerals.arabicToRoman(1));

}

}

We get this to compile with:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

return null;

}

}

Note that we’ve already applied the first transformation on the list: {}->nil. We apply the second transformation, nil->constant, to get to green:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

return "i";

}

}

Now we can add our second test:

public class RomanNumeralsTest {

@Test

public void arabicToRoman() {

assertRoman("i", 1);

assertRoman("ii", 2);

}

private void assertRoman(String roman, int arabic) {

Assert.assertEquals(roman, roman,

RomanNumerals.arabicToRoman(arabic));

}

}

The only way to make this test pass, is to introduce some conditional (unconditional->if):

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

if (arabic == 2) {

return "ii";

}

return "i";

}

However, this leads to duplication between the number 2 and the number of is returned. So let’s try a different sequence of transformations. Warning: I’m going into baby steps mode now.

First, do constant->scalar:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

String result = "i";

return result;

}

Next, statement->statements:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

result.append("i");

return result.toString();

}

Now we can introduce the if without duplication:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

if (arabic >= 1) {

result.append("i");

}

return result.toString();

}

And then another statement->statements:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

if (arabic >= 1) {

result.append("i");

arabic -= 1;

}

return result.toString();

}

And finally we do if->while:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

while (arabic >= 1) {

result.append("i");

arabic -= 1;

}

return result.toString();

}

Our test now passes. And so does the test for 3, by the way.

With our refactoring hat on, we spot some more subtle duplication: between the number 1 and the string i. They both express the same concept (the number 1), but are different versions of it: one Arabic and one Roman.

We should introduce a class to capture this concept:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

RomanNumeral numeral = new RomanNumeral("i", 1);

while (arabic >= numeral.getValue()) {

result.append(numeral.getSymbol());

arabic -= numeral.getValue();

}

return result.toString();

}

}

public class RomanNumeral {

private final String symbol;

private final int value;

public RomanNumeral(String symbol, int value) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.value = value;

}

public int getValue() {

return value;

}

public String getSymbol() {

return symbol;

}

}

Now it turns out that we have a case of feature envy. We can make that more obvious by extracting out a method:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

RomanNumeral numeral = new RomanNumeral("i", 1);

arabic = append(arabic, result, numeral);

return result.toString();

}

private static int append(int arabic, StringBuilder builder,

RomanNumeral numeral) {

while (arabic >= numeral.getValue()) {

builder.append(numeral.getSymbol());

arabic -= numeral.getValue();

}

return arabic;

}

Now we can move the append() method to RomanNumeral:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

StringBuilder result = new StringBuilder();

RomanNumeral numeral = new RomanNumeral("i", 1);

arabic = numeral.append(arabic, result);

return result.toString();

}

}

public class RomanNumeral {

private final String symbol;

private final int value;

public RomanNumeral(String symbol, int value) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.value = value;

}

public int getValue() {

return value;

}

public String getSymbol() {

return symbol;

}

public int append(int arabic, StringBuilder builder) {

while (arabic >= getValue()) {

builder.append(getSymbol());

arabic -= getValue();

}

return arabic;

}

}

We can further clean up by inlining the getters that are now only used in the RomanNumeral class:

public class RomanNumeral {

private final String symbol;

private final int value;

public RomanNumeral(String symbol, int value) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.value = value;

}

public int append(int arabic, StringBuilder builder) {

while (arabic >= value) {

builder.append(symbol);

arabic -= value;

}

return arabic;

}

}

There is one other problem with this code: we pass in arabic and builder as two separate parameters, but they are not independent. The former represents the part of the arabic number not yet processed, while the latter represents the part that is processed. So we should introduce another class to capture the shared concept:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral numeral = new RomanNumeral("i", 1);

numeral.append(conversion);

return conversion.getResult();

}

}

public class RomanNumeral {

private final String symbol;

private final int value;

public RomanNumeral(String symbol, int value) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.value = value;

}

public void append(ArabicToRomanConversion conversion) {

while (conversion.getRemainder() >= value) {

conversion.append(symbol, value);

}

}

}

public class ArabicToRomanConversion {

private int remainder;

private final StringBuilder result;

public ArabicToRomanConversion(int arabic) {

this.remainder = arabic;

this.result = new StringBuilder();

}

public String getResult() {

return result.toString();

}

public int getRemainder() {

return remainder;

}

public void append(String symbol, int value) {

result.append(symbol);

remainder -= value;

}

}

Unfortunately, we now have a slight case feature envy in RomanNumeral. We use conversion twice and our own members three times, so it’s not too bad, but let’s think about this for a moment.

Does it make sense to let the roman numeral know about an conversion process from Arabic to Roman? I think not, so let’s move the code to the proper place:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral numeral = new RomanNumeral("i", 1);

conversion.process(numeral);

return conversion.getResult();

}

}

public class RomanNumeral {

private final String symbol;

private final int value;

public RomanNumeral(String symbol, int value) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.value = value;

}

public String getSymbol() {

return symbol;

}

public int getValue() {

return value;

}

}

public class ArabicToRomanConversion {

private int remainder;

private final StringBuilder result;

public ArabicToRomanConversion(int arabic) {

this.remainder = arabic;

this.result = new StringBuilder();

}

public String getResult() {

return result.toString();

}

public void process(RomanNumeral numeral) {

while (remainder >= numeral.getValue()) {

append(numeral.getSymbol(), numeral.getValue());

}

}

private void append(String symbol, int value) {

result.append(symbol);

remainder -= value;

}

}

We had to re-introduce the getters for RomanNumeral‘s fields to get this to compile. We could have avoided that rework by introducing the ArabicToRomanConversion class first. Hmm, maybe refactorings have an inherent order too!

OK, on to our next test: 4. We can make that pass with another series of transformations. First, scalar->array:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

conversion.process(numerals[0]);

return conversion.getResult();

}

Next, constant->scalar:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

int index = 0;

conversion.process(numerals[index]);

return conversion.getResult();

}

Now we need an if:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

int index = 0;

if (index < 1) {

conversion.process(numerals[index]);

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

And another constant->scalar:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

int index = 0;

if (index < numerals.length) {

conversion.process(numerals[index]);

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

You can probably see where this is going. Next is statement->statements:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

int index = 0;

if (index < numerals.length) {

conversion.process(numerals[index]);

index++;

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

Then if->while:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

for (RomanNumeral numeral : numerals) {

conversion.process(numeral);

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

And finally constant->constant+:

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

RomanNumeral[] numerals = new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("iv", 4),

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

for (RomanNumeral numeral : numerals) {

conversion.process(numeral);

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

Now we have our algorithm complete and all we need to do is add to the numerals array. BTW, this should be a constant:

public class RomanNumerals {

private static final RomanNumeral[] ROMAN_NUMERALS

= new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("iv", 4),

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

ArabicToRomanConversion conversion

= new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic);

for (RomanNumeral romanNumeral : ROMAN_NUMERALS) {

conversion.process(romanNumeral);

}

return conversion.getResult();

}

}

Also, it looks like we have another case of feature envy here that we could resolve as follows:

public class RomanNumerals {

public static String arabicToRoman(int arabic) {

return new ArabicToRomanConversion(arabic).getResult();

}

}

public class ArabicToRomanConversion {

private static final RomanNumeral[] ROMAN_NUMERALS

= new RomanNumeral[] {

new RomanNumeral("iv", 4),

new RomanNumeral("i", 1)

};

private int remainder;

private final StringBuilder result;

public ArabicToRomanConversion(int arabic) {

this.remainder = arabic;

this.result = new StringBuilder();

}

public String getResult() {

for (RomanNumeral romanNumeral : ROMAN_NUMERALS) {

process(romanNumeral);

}

return result.toString();

}

private void process(RomanNumeral numeral) {

while (remainder >= numeral.getValue()) {

append(numeral.getSymbol(), numeral.getValue());

}

}

private void append(String symbol, int value) {

result.append(symbol);

remainder -= value;

}

}

Retrospective

The first thing I noticed, is that following the TPP led me to discover the basic algorithm a lot quicker than in some of my earlier attempts at this kata.

The first thing I noticed, is that following the TPP led me to discover the basic algorithm a lot quicker than in some of my earlier attempts at this kata.

The next interesting thing is that there seems to be an interplay between transformations and refactorings.

You can either perform a transformation and then clean up with refactorings, or prevent the need to refactor by using only transformations that don’t introduce duplication. Doing the latter is more efficient and also seems to speed up discovery of the required algorithm.

Certainly food for thought. It seems like some more experimentation is in order.

Update: Here is a screencast of a slightly better version of the kata:

There seems to be some confusion between Test-First Programming and Test-Driven Development (TDD).

There seems to be some confusion between Test-First Programming and Test-Driven Development (TDD). In the first TDD phase we write a test. Since there is no code yet to make the test pass, this test will fail.

In the first TDD phase we write a test. Since there is no code yet to make the test pass, this test will fail. We may evolve our code using simple

We may evolve our code using simple  All in all I think Test-Driven Development provides sufficient value over Test-First Programming to give it a try.

All in all I think Test-Driven Development provides sufficient value over Test-First Programming to give it a try. One of the important things in a

One of the important things in a  The process outlined above works well for making our software ever more secure.

The process outlined above works well for making our software ever more secure. Some people object to the Zero Defects mentality, claiming that it’s unrealistic.

Some people object to the Zero Defects mentality, claiming that it’s unrealistic. The

The

Lots of courses are being offered, many of them conveniently online. One great (and free) example is

Lots of courses are being offered, many of them conveniently online. One great (and free) example is  You can organize that a bit better by doing something like job rotation. Good forms of job rotation for developers are

You can organize that a bit better by doing something like job rotation. Good forms of job rotation for developers are

There are many ways of testing software. This post uses the

There are many ways of testing software. This post uses the

Last time, we saw how

Last time, we saw how

You must be logged in to post a comment.