Explore DDD is a two-day conference about Domain-Driven Design (DDD) in Denver, Colorado, that my employer VelocityEHS was kind enough to let me go to. Below, I give an impression of the sessions that I attended.

Wednesday

Opening keynote: Diana Montalion

Diana spoke about how systems thinking can inform architecture. In complex adaptive systems, the relationships between the parts that make up the system are actually more important than the parts themselves, leading her to claim that “architecture is relationship therapy for software systems.”

Because of non-linear dynamics, there are often leverage points in systems, where a small shift produces significant, lasting change. However, people won’t believe you if you find one, so it makes sense to let them discover patterns for themselves by building an easily accessible knowledge graph.

DDD & LLM brainstorming: Eric Evans

Eric led a two-hour workshop where we explored how LLMs can help with DDD. We crowdsourced topics and discussed them in groups.

My group worked on the concept of a DDD linter, which would work off a glossary to help team members use the ubiquitous language properly.

The group set up a Discord server to continue after the conference, hopefully producing an actual tool at some point.

Strategies for Fearlessly Making Change Happen: Mary Lynn Manns

In this workshop, we got to play the Fearless Journey game. We started by defining the as-is and desired to-be states. Then we defined obstacles that may prevent us from reaching that goal. Each obstacle went into a bag and we took them out one by one in random order. We used one or more of the 60+ fearless change pattern cards to attack the obstacle.

This session connected several dots for me, which I may write about later.

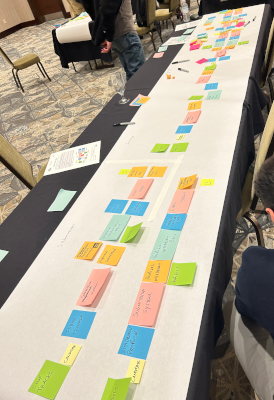

The EventStorming Process Modelling Rat Race: Alberto Brandolini & Paul Rayner

In this workshop I got to practice the process modeling variant of event storming on the problem of selecting talks for a conference. It was set up as a competitive game, where teams worked on the problem in 3 rounds of 20 minutes, with scoring and small retrospectives.

I got to ask Alberto himself some in-depth questions about how he uses event storming in practice.

Thursday

Systems Theory and Practice Applied to System Design: Ruth Malan

In this workshop, Ruth helped us apply some systems thinking tools to a toy problem. Examples are bubble diagrams and concept cards. One of the main lessons learned is to always design a system in its next larger context, e.g. a design a chair in a room, or a room in a house, since the system’s properties interact with the system’s context.

Another lesson is to record decisions are review them later, both when an issue arises and periodically. This helps see how decisions play out over time and fosters learning.

Teaching DDD – Facilitating Mindset Shifts: Tobias Goeschel

In this workshop, Tobias led us through an interesting approach to solving the problem of introducing a new technique to people who may not care about the technique per se.

We first identified job roles of people we may want to influence and placed them on a diagram with two axes: engine room → c-suite and technical → non-technical. We identified the 3 top things these people care about and brainstormed facts about the technique that impact these things.

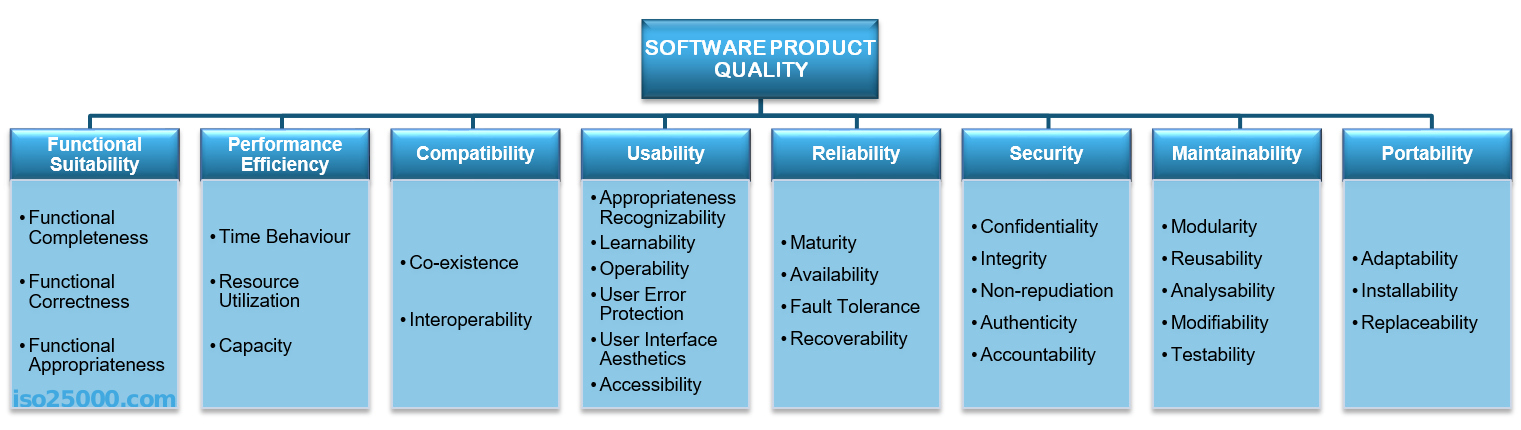

We then identified the tools that come with the technique, like ubiquitous language or context mapping for DDD, and placed these on a similar diagram. The combination of the two diagrams shows what tools are likely to be of use for a given role.

Learning from Incidents as Continuous Design: Eric Dobbs

In this workshop, Eric taught us about the Learning From Incidents (LFI) community. It’s easy to spot errors in hindsight, but it’s much more difficult to encourage insights. We like to attribute the “root cause” to human error, so we have someone to blame. It’s much harder to see how the system enabled the human to make that error, because we can’t see the system directly, but only through representations.

After the theory, we applied some DDD techniques to the incident response process. I always love it when people combine different fields.

Closing keynote: Rebecca Wirfs-Brock

Rebecca talked about the various degrees of rigor a DDD model can have and how much rigor to apply in what situation. She gave examples of not enough rigor (Boeing 737 Max) and too much (limiting people’s names, like rejecting non-letter characters or characters with accents). Since my legal name is Rémon, I certainly could relate to the latter.

Conclusion

I absolutely loved this conference! The hands-on sessions gave me something that’s hard to get anywhere else: practical application of ideas under the guidance of experts in the field. As many people can attest, reading about e.g. event storming is very different from actually doing it.

I also loved the networking opportunities. At lunch on Wednesday I sat next to the InfoQ editor for Architecture & Design, and on Thursday to µservices master Chris Richardson. (And the food was good too.)

The breaks in between sessions were 30 minutes, which gave me enough time to strike up some good conversations.

And to top it all of, Diana Montalion gave me a free, signed copy of her book!

Many thanks to Paul Rayner and team for organizing! Hopefully they can manage to put together another conference next year 🤞

You must be logged in to post a comment.